Mastering the Art of Classroom Questioning

Leave a commentOctober 29, 2018 by twunewteachers

Asking questions is a fundamental practice in all classrooms. Teachers ask questions to clarify, extend, or probe learning. Teachers ask questions to check and see if students are tracking during a lesson and whether they are getting it so that the lesson can keep moving. Teachers also ask questions to facilitate procedures and routines in the classroom and to ensure smooth learning transitions. Questioning, no doubt, is a crucial piece of the learning puzzle.

But imagine this scenario:

Mrs. Trying-Hard is teaching a lesson on the causes of geographical changes on the earth. She reviews previous learning with students by asking questions of the whole class. Several students sitting at the front repeatedly raise their hands to answer. These students seem to be the only ones participating. The rest of the class looks zoned out or confused. One student at the back raises his hand, but is completely off with his response, so Mrs. Trying-Hard moves on to the next student. Additionally, she realizes that she is asking only basic, remember questions and is not really getting to the heart of her lesson – having students explain and rationalize the changes that occur. But the bell is about to ring and students will go to their next class, so Mrs. Trying-Hard has to keep pushing through the lesson.

Is this scenario vaguely familiar? If it is, you are not alone, as many teachers – new and veteran – struggle with how to effectively question students to promote learning. This blog post will focus on some simple strategies and reminders to better facilitate active engagement, deepen student thinking, and promote cognitive processing when questioning students.

Wait Time

Quite often, teachers are pressed for time and the temptation to “just keep the lesson moving” becomes the most realistic objective. These teachers succumb the behavior of rapidly asking questions, calling on the first hand that is raised, and then quickly moving on to the next part of the lesson. But what truly facilitates learning is wait time, sometimes known as think time. When teachers ask a question, there will inevitably be a few students who will be ready with an immediate answer. But what about everyone else in the class? These students typically need time to simply process the question before retrieving or formulating a response. There are lots of ways to incorporate wait time. Teachers can implement a counting strategy, can tell students to wait until “go” to raise their hands, or can use a timer. The teacher in this video, is a pro at implementing wait time. Notice how the number of voluntary contributions increases the more time that is given.

Implementing wait time transitions the focus from simply getting through a lesson to facilitating deep understanding, which should be the ultimate end goal of any lesson. What are some other strategies that you’ve tried to increase wait time in the classroom?

Increase Participation

While whole-group classroom questions are some of the simplest ways to check how students are grasping new material, it is somewhat limited because only one student can actively participate at a time. Teachers can instead increase participation to include more learners by using grouping strategies such as turn and talk, think-pair-share or mix-it-ups where students have to find a partner and then discuss a concept. These strategies, paired with wait time, are especially effective at increasing cognitive processing among all students. While students share, the teacher can walk around the room, and monitor both participation and responses to ensure students are on the right track with their thinking. When all students actively participate, learning goals are maximized. For more great ideas on actively engaging the whole class through questioning, check out this brief podcast on Total Participation Techniques.

https://thecornerstoneforteachers.com/truth-for-teachers-podcast/total-participation-techniques/

Probing, Prompting, Providing Cues

Planning questions in advance and preparing for how students will respond are great ways to enhance classroom questioning techniques. Teachers typically do a great job of planning for the answers based on their own suppositions of the lesson, what was taught, and what students should know. But what happens when a student responds to a question with an off-the-wall response? What next? Quite simply, teachers must refine and implement their questioning skills through probing, prompting, and providing cues. Probing allows teachers to get to the bottom of students’ thinking by asking follow-up or clarifying questions. For example, questions such as, “Why do you think that? Explain your thinking? or How did you get that answer?” are great ways to further explore student thinking. Verbal prompts and visual cues are also effective strategies to help provide students with the scaffolding needed for them to think through the question individually. Effective teachers are able to use hints, reminders, visual cues, anchor charts, strategies to rephrase questions, and other great probing strategies to help provide those supports. This typically takes a little bit of practice to master, but the pay off with student ownership is worth it in the long run. It is definitely better than a teacher having to answer the question or calling on another student to “help the student out.” Students should always be provided with opportunities to master their own learning and save face when they don’t get it the first time. As a last resort, when you have prompted and prodded, and students are still not able to answer your questions, you might need to stop and re-teach or re-evaluate the techniques that you are using.

Spiraling Technique

If you remember anything from your teacher education courses or preparation, chances are you remember learning about Bloom’s Taxonomy and the importance of asking higher level questions. You have probably even tried to throw in those high-level, evaluate and synthesis questions, especially when your administrator drops in to watch you teach. But what is often misunderstood about the importance of high level questions, is the equal importance of the foundation to get there. If you throw out a very high level question right off the bat, your students will most likely struggle to answer it. Instead, teachers should use low-level questions to build the foundation, ensure mastery of basic facts and understandings needed to understand the high-level concept, and then gradually work their way up to asking the complex, critical thinking questions. This technique is known as spiraling. Through this process, teachers start by asking low-level questions while gradually using student responses and previous learning to build up to the complex, higher levels on Bloom’s Taxonomy. Keep in mind that the end goal is critical thinking and low-level questions are only a small piece of this puzzle. I use the following illustration in my teacher prep courses when introducing teachers to the concept of spiraling:

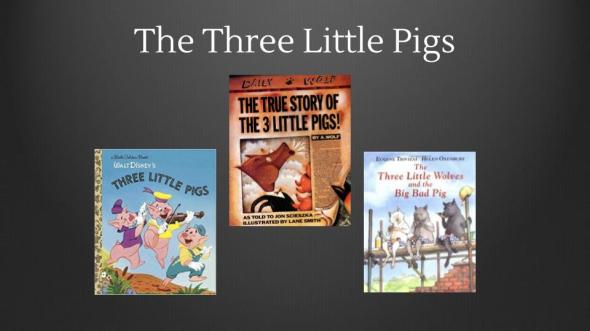

Most students are familiar with various versions of the children’s book, “The Three Little Pigs” and corresponding instructional activities where students have to compare and contrast the different viewpoints. I use this resource to illustrate the different levels of questions/tasks on Bloom’s Taxonomy and how low-level questions can serve to build to the higher level ones. For example, if you were doing a mini-unit on these books, and started off by asking, “What would happen if we were to write a new story where neither the wolf and the pig were good guys?” students would probably not understand what you were asking them to do. But if you were to take them through the following illustration and build up to the high level question or task, students would probably be able to complete this quite well.

The beauty of spiraling is giving students mastery on lower-level, lower-risk questions to build both the confidence and mastery to be able to think critically. Another great resource on this topic is a 20-minute video called, “How to Spiral Questions to Provoke Student Thinking” produced by the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development site (ASCD). This video is available for digital streaming or on DVD and your campus professional library might be able to purchase it for professional development purposes:

http://www.ascd.org/ascd-express/vol4/418-video.aspx

With practice, teachers can easily master the technique of asking questions to students. In a future blog release we will continue this topic and focus on how to transition from being the one asking questions to the one facilitating questions and discussion from students.

What are some other great strategies that you use to question your students on learning concepts?